For 40 long years, she was buried without a name.

A young woman, brutally murdered, laid to rest in a California cemetery, labeled only as “Jane Doe No. 5.” No one knew who she was. No one could say where she came from. But someone remembered her. Someone never stopped looking.

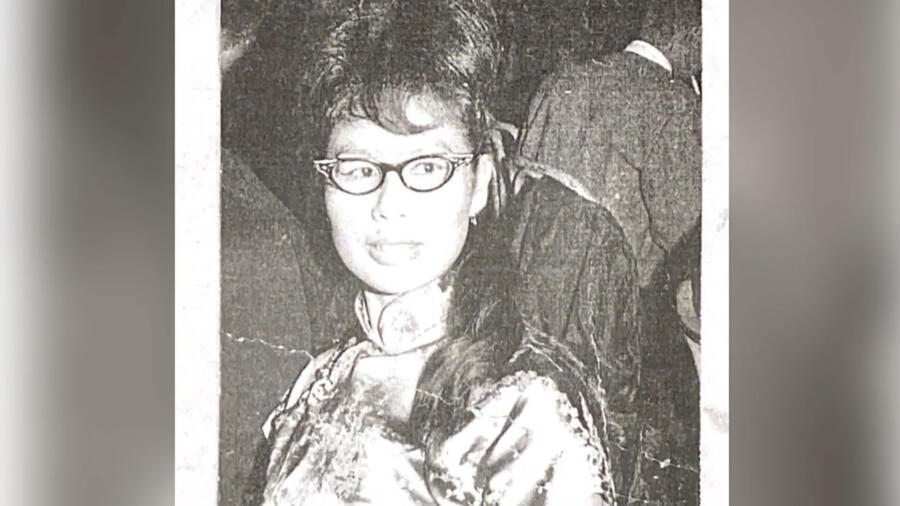

Her name was Shirley Ann Soosay—a 26-year-old Cree woman from Maskwacis, Alberta. She was loved. She mattered. And thanks to a powerful blend of science and love, she finally got her name back in 2020.

A Brutal Crime, A Forgotten Victim

On July 10, 1980, in a quiet almond orchard in Kern County, California, a farmworker discovered a horrifying scene: the body of a woman, stabbed 27 times, sexually assaulted, and discarded like trash.

Just days later, another woman, also raped and stabbed—this time 20 weeks pregnant—was found in Ventura County, left in a school parking lot. The similarities were chilling, but no connection was made. Both women were buried without names, their cases fading into the background of an overwhelmed justice system.

DNA Reveals a Killer—but Not Their Names

Years passed. And then, in 2008, DNA changed everything.

Wilson Chouest, a convicted serial rapist, was linked through DNA evidence to the Kern County and Ventura County victims. His past was terrifying:

- 1977: Raped and strangled a woman who survived

- 1980: Released just weeks before the murders

- 1981: Convicted again for another brutal attack

In 2015, Chouest was arrested. In 2018, he was convicted of two counts of murder. But even after the verdict, the victims remained officially unidentified. In every document, every headline, they were still listed as Jane Does.

A Family’s Hope—and a Breakthrough Through DNA

While Chouest served life in prison, the question remained: Who were these women?

That’s when the DNA Doe Project, a volunteer nonprofit team of genetic genealogists, took on the case. They carefully reconstructed a family tree using DNA from the Kern County Jane Doe, hoping it would lead to someone—anyone—who knew her.

By 2019, they had narrowed her origins to Indigenous communities in Alberta, Canada. That’s when Violet Soosay, a woman from Maskwacis, saw the public appeal.

She had been searching for her aunt, Shirley, for decades.

She submitted her DNA. And it matched.

Who Was Shirley Ann Soosay?

Shirley was a vibrant, kind-hearted 26-year-old Cree woman. She traveled from Canada to California in the late 1970s, full of hope and independence. Then she vanished.

Her family never gave up. For years, they searched, prayed, and wondered—until DNA finally brought her home.

“She was loved. She was missed. And now, she is remembered,” said her niece, Violet Soosay.

More Than a Name: A National Crisis

Shirley’s story isn’t just about justice delayed. It’s about a systemic tragedy.

Her case is part of the MMIWG2S crisis—Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people. Across North America, thousands of Indigenous women go missing or are murdered every year. Most cases go unsolved. Many victims remain unidentified. And too many families are left with silence instead of answers.

Shirley’s case was one of the first solved through forensic genealogy for an Indigenous woman. But she won’t be the last—if families come forward, if communities demand justice, and if we all care enough to say their names.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Shirley Ann Soosay?

She was a 26-year-old Cree woman from Maskwacis, Alberta, murdered in California in 1980 and unidentified until 2020.

How was she identified?

Through forensic genetic genealogy and a DNA match submitted by her niece, Violet Soosay.

Who killed her?

Wilson Chouest, a serial rapist, was convicted in 2018 of her murder and another woman’s. He is serving life in prison.

What is the DNA Doe Project?

A nonprofit that uses forensic genealogy to identify unknown murder victims and return names to Jane and John Does.

What is MMIWG2S?

A movement to raise awareness of the thousands of Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people who have gone missing or been murdered—many without resolution.

Why was Shirley not identified sooner?

She had no ID, her family lived in another country, and police were not actively connecting Indigenous missing persons with unidentified remains at the time.