For four long years in the 1990s, the city of Charlotte, North Carolina, lived under a chilling shadow. Henry Louis Wallace—dubbed “The Charlotte Strangler” and “The Taco Bell Strangler”—quietly preyed on his victims while managing a fast-food restaurant. He didn’t lurk in alleyways or strike at random. Instead, he exploited relationships, slipping into the homes of women he knew, women who trusted him. Tragically, he raped and murdered 11 Black women—friends, coworkers, even close acquaintances—before police finally caught him.

A Predator Hiding in Plain Sight

Wallace didn’t fit the stereotype of a serial killer. He presented himself as a calm, intelligent man—articulate, friendly, and reliable. As a restaurant manager, he maintained close relationships with many of his victims. Several of the women he killed had worked for him. This familiarity allowed him to enter their homes without suspicion.

He manipulated their trust, often visiting unannounced, then turning violent once inside. To cover his tracks, Wallace took calculated steps. He wiped fingerprints, forced victims to shower to eliminate DNA, and placed incriminating items inside ovens to destroy evidence. Despite the brutal nature of his crimes, his charm and lack of a criminal profile helped him fly under the radar.

The Mounting Murders and Missed Connections

The first known murder occurred in March 1990. Eighteen-year-old Tashanda Bethea was found strangled and dumped in a pond in South Carolina. Wallace soon moved to Charlotte, where his violence escalated. Between 1992 and 1994, he murdered 10 more women, many of whom lived within blocks of each other.

Yet, law enforcement failed to connect the dots. One major reason? The city was overwhelmed. In 1993 alone, Charlotte recorded 129 homicides, many driven by the crack epidemic. The homicide division, struggling with limited staff and increasing cases, simply didn’t have the resources to dig deeper. Only six to eight detectives managed all investigations—from natural deaths to complex murder cases.

Overburdened Police, Underprotected Women

Detective Garry McFadden, now sheriff of Mecklenburg County, admitted how thinly the team was stretched. With little time and even fewer leads, murders involving Black women received less attention. Wallace’s victims all shared similar traits—they were Black, young, and often from lower-income backgrounds. Unfortunately, society often undervalues these lives.

Dee Sumpter, the mother of one of Wallace’s victims, helped co-found the group Mothers of Murdered Offspring. She pointed out that authorities ignored patterns because the victims weren’t white. That oversight, mixed with racial bias and a swamped homicide unit, allowed Wallace to kill again and again.

Dark Roots: Wallace’s Troubled Past

Born in 1965 in Barnwell, South Carolina, Henry Louis Wallace faced trauma early. Raised by a single mother who beat and emotionally abused him, he grew up with little stability. At eight, he witnessed a horrific gang rape—an event that deeply warped his perception of women and intimacy. By high school, Wallace was popular and academically successful, but his hidden thoughts turned darker.

In 1987, while living in Washington state, he committed his first known rape. That act marked the start of his violent spiral. Despite previous accusations of assault, he continued to evade serious consequences. This leniency emboldened him.

The Victims: A Community in Mourning

Each of Wallace’s 11 victims had a story, a family, and dreams. Many of them worked together, lived near each other, and shared mutual friends. Some had children. One victim’s infant was found alive next to her body, a cruel reminder of Wallace’s calculated brutality.

Particularly heartbreaking was the murder of Shawna Hawk. After her death, her mother, Dee Sumpter, became an outspoken advocate for crime victims. Wallace even attended Hawk’s funeral—grieving with the family while hiding his guilt. His presence shocked friends who later learned he was the killer.

The Break That Changed Everything

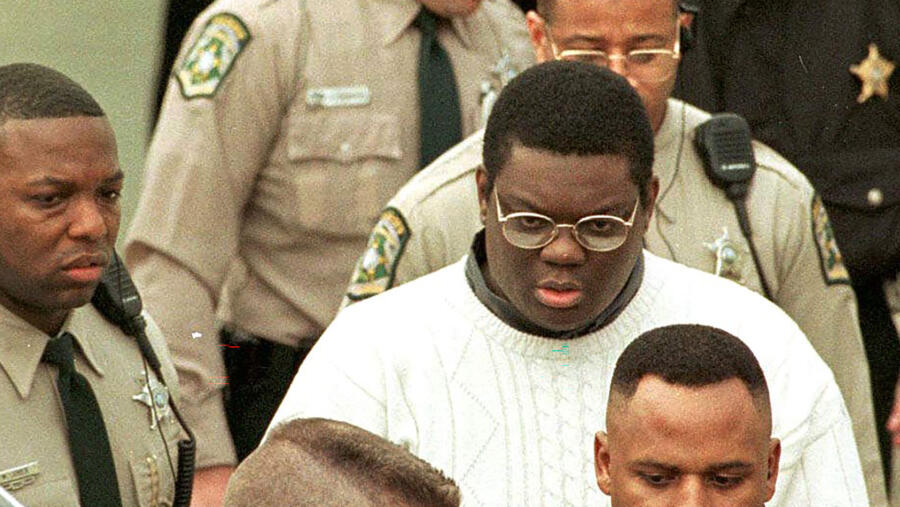

Wallace’s careful efforts to avoid detection began to unravel in March 1994. When two women were murdered within days of each other in the same apartment complex, suspicions deepened. Detectives found a crucial palm print on Betty Jean Baucom’s car. That print matched Wallace.

After tracing the print and comparing it with previous crime scene clues, police identified Wallace. His mugshot, which showed his signature cross-shaped earring, sealed the match. Arrested on March 13, 1994—just one day after his last murder—Wallace quickly confessed to the killings.

Why Did It Take So Long?

Police finally caught Wallace after years of unchecked murder. But why did it take 11 lives?

The answer lies in a mix of systemic failure, racial bias, and limited resources. Investigators often didn’t connect murders because they happened in different parts of town or seemed unrelated. The victims’ profiles—young Black women, some with minor records or linked to low-wage jobs—led to apathy from both media and law enforcement.

Detective McFadden later admitted that if the victims had been white, the case might have taken a different path. Studies support this. While most serial killers in media are portrayed as white, research shows that 13–20% are Black. Serial crimes often go unsolved when the victims come from marginalized groups.

Reform and Reflection

Wallace’s arrest marked a turning point for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department. The department expanded its homicide unit dramatically and restructured its investigative processes. Officers began receiving specialized training on recognizing patterns in serial killings and working with diverse communities.

Trust-building with victims’ families became a priority. Community advocates like Dee Sumpter pushed for better outreach, more empathy from law enforcement, and stronger communication with the families of the missing and murdered.

Where Is Wallace Now?

In January 1997, a North Carolina jury convicted Wallace of nine murders. He received the death penalty along with convictions for rape, robbery, and sexual offenses. Currently, he remains on death row.

Even in prison, his case continues to stir public debate. Critics point out how long it took to stop him. Advocates use the case to highlight the importance of equitable treatment in criminal investigations, regardless of race or class.

A Haunting Legacy and Lessons for the Future

Henry Louis Wallace’s case stands as a stark reminder: serial killers don’t always fit a mold, and their victims don’t always receive equal attention. His reign of terror, cloaked in familiarity and hidden behind a smile, left deep scars on Charlotte. More than that, it exposed the need for reform—in law enforcement, in media coverage, and in how society values Black lives.

Thanks to pressure from community leaders and the families of the victims, real change began. But the pain of those lost can never be undone.

FAQs

Who was Henry Louis Wallace?

Henry Louis Wallace was an American serial killer who murdered 11 women in Charlotte, North Carolina, between 1990 and 1994.

Why was Henry Wallace called the ‘Taco Bell Strangler’?

He earned the nickname because many of his victims worked at the Taco Bell restaurant he managed, where he used his position to target them.

How did Wallace avoid capture for so long?

A combination of systemic police failures, racial bias, and resource shortages allowed him to operate undetected for years.

Did Wallace show any remorse?

After his arrest, he confessed but never publicly showed genuine remorse, often speaking about the murders in a detached manner.

How did the case impact law enforcement in Charlotte?

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department expanded its homicide unit and overhauled its investigation procedures in response to the Wallace case.

Is Henry Louis Wallace still alive?

Yes, as of 2025, Henry Louis Wallace is alive and remains on death row in North Carolina.