A Killer’s Rise to Public Sympathy

In 1971, Edgar Smith walked out of prison after serving over 14 years. Convicted of murdering 15-year-old Victoria Zielinski in 1957, he had once confessed. Yet, years later, he managed to spin a new story—one that fooled even the sharpest minds, including William F. Buckley Jr.

The Crime That Started It All

Victoria Zielinski’s murder stunned the quiet town of Mahwah, New Jersey. Investigators found her bludgeoned with rocks and a baseball bat. Edgar Smith quickly became the main suspect. Initially, he confessed. That confession seemed to seal the case.

From Inmate to Author: Smith’s Plot Unfolds

While sitting on death row, Smith launched a bold plan. He began writing, not just letters—but arguments. He filed over a dozen appeals. Then, he published Brief Against Death, a book claiming his innocence. His prose persuaded readers that the justice system had failed him.

Buckley’s Attention Turns the Tide

William F. Buckley Jr., the conservative icon and founder of National Review, noticed Smith’s letters. Smith admired the magazine. That detail led Buckley to correspond with him. The prisoner’s sharp intellect impressed Buckley, who soon became convinced of Smith’s innocence.

Buckley used his platform to amplify Smith’s claims. He raised money, wrote op-eds, and persuaded others to take a second look. Buckley’s voice carried weight—and it made people listen.

The Legal Twist That Freed a Killer

Thanks to Buckley’s advocacy and new Supreme Court rulings, Smith’s confession faced scrutiny. Eventually, a judge vacated the conviction. Rather than fight another trial, Smith took a plea deal—non vult contendere, meaning no contest. This allowed him to go free with time served.

A Celebrity’s Life Post-Prison

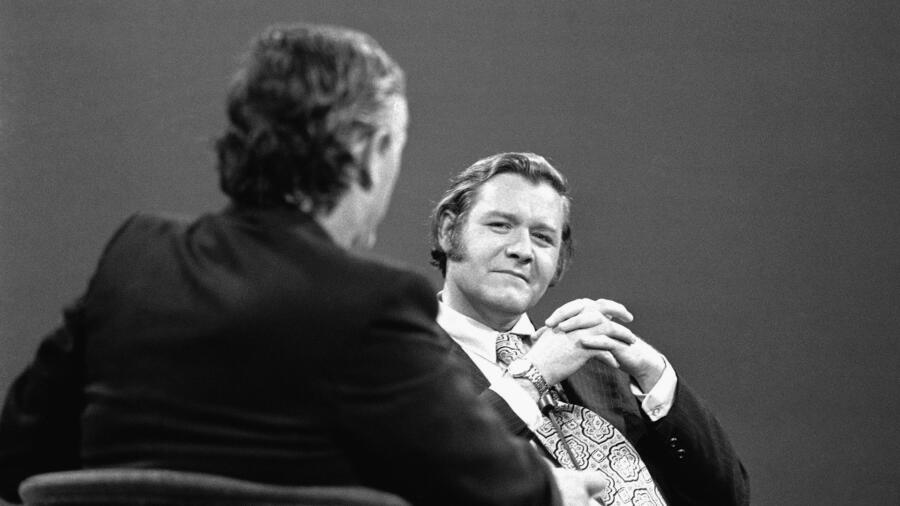

After his release, Smith became a media figure. He appeared on Firing Line beside Buckley. Reporters wrote about him. He moved to California, remarried, and gave lectures on justice reform. For a time, people celebrated him as a wrongly accused man turned activist.

A Violent Relapse Reveals the Truth

But in 1976, Smith attacked another woman, Lefteriya Ozbun. He stabbed her repeatedly. Thankfully, she escaped. This time, the evidence left no doubt. Smith confessed—not just to the new crime, but to Victoria Zielinski’s murder as well.

“I was the devil I’d been trying to hide,” he admitted in court.

The Minds He Fooled

Smith’s case reveals how charisma and intelligence can mislead. Buckley, a sharp thinker, couldn’t reconcile Smith’s eloquence with the crime. Psychologists warn about this trap—confusing verbal skill with moral integrity.

Sarah Weinman, author of Scoundrel, explored this dynamic. She explained how Smith’s writing could persuade even skeptical readers.

An Admission That Came Too Late

After Smith’s second arrest, his supporters felt betrayed. Jack Carley, a former student who had helped his defense, later reflected on their mistake. “We were wrong,” he said. “But we believed because we cared.”

Even Buckley admitted the truth in private. He later helped authorities track Smith down. The man he once defended had proven himself guilty—twice.

The Silence That Spoke Volumes

After Smith’s second conviction, Buckley stopped discussing the case. He wrote one final article, then moved on. That silence said everything. It marked a deep personal regret from a man rarely at a loss for words.

What the Edgar Smith Murder Case Teaches Us

This story isn’t just about one killer. It’s about how power, personality, and performance can override facts. Smith’s charm blinded many. His case reminds us to stay cautious, especially when truth hides behind eloquent lies.

FAQs

Who was Edgar Smith?

A convicted murderer who manipulated public figures into helping overturn his conviction.

What crime did Edgar Smith commit?

He murdered Victoria Zielinski in 1957 and later attacked another woman in 1976.

Why did people believe Smith?

His articulate writing and persuasive tone convinced many that he had been wrongfully convicted.

How did William F. Buckley Jr. get involved?

Smith’s letters and writings impressed Buckley, who then became a vocal supporter.

What happened after Smith’s release?

He attacked another woman, confessed to both crimes, and was imprisoned again.

Did Buckley regret supporting Smith?

Yes. After Smith’s confession, Buckley expressed regret and never spoke of the case again.